Chapter 6: Robert "Harlequin Bob" Cowburn.

- Catherine Leung

- Oct 24, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 27, 2021

"Learn this now and learn it well. Like a compass facing north, a man's accusing finger always finds a woman. Always. You remember that, Mariam."― Khaled Hosseini, A Thousand Splendid Suns"."

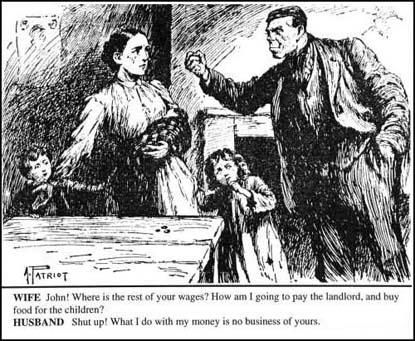

The laws in Britain were based on the idea that women would get married and that their husbands would take care of them. Before the passing of the 1882 Married Property Act, when a woman got married her wealth was passed to her husband. If a woman worked after marriage, her earnings also belonged to her husband.

On December 3, 1830, Mary married Constable Robert Cowburn, a former convict. Why she married Cowburn is guesswork. He seemed persistent, applying three times for permission to marry her. She may have wanted to escape her misery in the Factory. The work and conditions in the Cascades Factory were harsh. Situated in the shadow of Mt Wellington, the prison was cold and damp, and third-class prisoners spent 12 hours a day doing heavy manual labour. Cowburn was offering a way of escape.

His career as a constable was hardly stellar. His drinking and violence continued.

After failing to marry Ann Carnes, he applied for permission to marry Mary Davis in 1828, with Mary's poor record, the application was denied twice. Permission to Marry was finally given in 1830 after Cowburn entered into the Field Police. Mary bore him two children, little Mary in 1832 and Sarah in 1834.

Cowburn continued to abuse his position as a constable. Four months after the wedding in February 1831, he assaults and beats Thomas Laing (Lang). A hardened criminal, Lang is scarred from 370 lashings and hard labour on road gangs. He was a constant absconder, earning himself hard labour on the road gangs. Convicted of Burglary in 1822, he was sentenced to life. He left a wife and three children behind in Manchester. As overseer on the gang, Cowburn beats Lang savagely for not filling a water bucket. Cowburn is fined for bashing Lang.

Cowburn's violent behaviour escalates. He was before the courts again in June 1831 charged with murder. Cowburn and another beat an older man Morris to death with a bludgeon. After a short period in the Richmond Goal, he is acquitted. The coroner concluded Morris had died of a heart attack. But, again, witnesses failed to appear.

He continues to come before the courts on assault, drunkenness, and theft during 1832. Lack of evidence or witnesses sees many of these offences dismissed. At most, a small fine is levied. Given the standover tactics of the Field Police, few witnesses would dare come forward.

Newspaper records of Cowburn's drunkenness and violence.

It does not take much imagination to see Mary as a victim of domestic violence. Mary left the relationship sometime in 1836-7. Cowburn's brutish character is commented on in 1855 during the inquest into the death of a woman named Elizabeth Cowburn. She was living in a hut with Cowburn at the time of her death. The only transport was by foot or ferry.

Coroner's Inquest into Elizabeth's Death

On the 26th instant, a jury of seven was empanelled at the Sand Spit, Lower Ferry, near Sorell, before Charles Eardley-Wilmot, Esquire, Coroner, to inquire, into the circumstances attending the death of Elizabeth Cowburn, wife of Robert Cowburn, better known as "Harlequin Bob." The jurors having been sworn, with the coroner, viewed the body in a miserable hut at the water's edge. Still, the effluvia were so insufferable that part of their duty was only for an instant. The first witness was Robert Cowburn, who deposed that he was the deceased's husband, who was 48 years old. On Tuesday morning, he left home, the 20th instant, for Sorell, about 8 miles distant, when the deceased complained of a pain in the back part of her head. Witness told her he should return in the evening of the same day, or the next morning. Deceased begged to do" saying, "I hope you will, as I do not "feel well."

Coroner: When did you return home? Witness: On Sunday morning, the 26th of this month. Coroner: Was the deceased all alone? Witness: Yes, sir Coroner: Where did you spend the time? Witness: I spent part of the time in public-houses and part at my son-in-law's.

Witness then stated that he knocked at the door on reaching home, but receiving no answer, he got into the hut when he found his wife dead, and from her position had been attempting to get out of bed.

Thomas Purton stated that he saw the deceased on Wednesday night in her hut, when she appeared in her usual health and complained of having neither tea nor sugar', adding 'if my husband comes home, I'll bolt."

Dr Westbrook said he had made a post-mortem examination of the body of the deceased woman. On opening the head, he discovered about three tablespoonsful of fluid between the brain's hemispheres, which might be produced from frequent intoxication, debility, or an over-enervated state of the system. He believed that the cause of death was serous apoplexy (a stroke).

The coroner then proceeded to sum up the evidence. He said it was pretty notorious in the district that both the husband and the unfortunate woman, the cause of whose melancholy death they (the jury) had assembled to ascertain, had been for a long series of years given to habitual habits of intemperance, that great curse of the colony, but although the evidence did not inculpate the husband as having been the cause of his wife's death by violent means. Yet, at any rate, he had been guilty of the most heartless neglect in leaving a sick wife in a lonely hut without a friend to minister to her necessities, for five whole days, while he was indulging in sottish drunkenness. For aught, he (the coroner) knew, debauchery, in the township. Even that circumstance of itself was truly shocking, and such brutality as he [ the coroner] was sorry there was no human law to punish

After Mary disappears and Elizabeth dies, Cowburn marries widower Catherine Bloomfield in 1865. Cowburn died in 1873 at the age of 75. He leaves a wife and six children. They had been living on a paupers allowance of 10/- per week. Once again, Cowburn makes the local paper.

Another name has dropped from the Sorell pauper list: Robert Cockburn, who died on Sunday last in his 75th year, will no longer require the aid of a charitable Government. However, the death of a pauper does not invariably lessen the draft on the public purse but, on the contrary, very frequently increases it. Of this fact too often overlooked by frothy political declaimersCockburn's death affords it a striking illustration. He leaves behind him six children, of age varying from ten years to three months, entirely dependent upon their mother, who can scarcely keep herself. The result most probably will be that, whilst with the death of Cockburn, his weekly allowance of 10s will cease, these six children will be for some time a burden on the State and the Queen's Asylum, at an annual cost of £15 0s, 6d per annum each. Thus pauperism, upas-like, overspreads the country and, like the Californian thistle, cannot be rooted out. "It is strong, in death and does not die without issue". Cockburn's history, better known as "Harlequin Bob," was a chequered and eventful one. He was a soldier in the 6th Regiment of Foot in the Army of Paris after Waterloo. He was one of three who, together with the "Pieman", made their escape from Macquarie Harbour and, after subsisting on grass, &c, &c, surrendered themselves at Port Davey in 1823. He was constable to Governor Arthur when the "Black Line" was out, and present with him at the end of the line in this district. He subsequently served in various detective capacities, and, where his life written, as he himself has frequently said, it would "a tale unfold." However, he has now passed it is to be hoped to that place, "where the wicked ceases from troubling, and the weary are at rest."

A little fact-checking would have revealed that Cowburn was never in the Army, and he was a teller of tall tales. He never went to Macquarie Harbour's infamous Sarah Island prison and would never have met the cannibal, Alexander Pearce, who was hanged in July 1824. Perhaps he had a hand in the Black Line fiasco, a six-week campaign to drive the local indigenous peoples out of the way. However, he was getting married and arrested for drunkenness around that time. If, as a constable, he played a part, it would have been a minor one. Reading the many newspaper articles about Harlequin Bob, it is obvious he is prone to exaggeration.

Mary had left the marriage sometime after the birth of Sarah in 1834, and the birth of her third daughter Mary Ann Hatfield was born on 10 August 1837. Mary Ann was born in Woodside, South Australia.

Mary left Cowburn's two daughters, aged three and four years of age. She was a convict when she married Cowburn,and perhaps a measure of her desperation to escape prison life. It is a mystery as to why she left the children behind. She was a free woman in 1831. When she began her affair with Joseph Hatfield is unknown. There is no record of her arrival in South Australia. Her new partner must have offered her a fresh start, and she took it, even if at the price of her two girls.

Mary's daughters did not flourish, and their lives were full of trouble and short. Mary, born February 7 1831, married convict Frederick Phipps. Mary was 15 years old when she married 38-year-old Phipps, a"Lifer" convicted for burglary and vagrancy. When Phipps died on January 12 1862, from natural causes, his occupation was "Farmer". Together they had two children Henry born in 1847, and Mary Ann, born in May 1850. Mary died on December 15 1862, twelve months after her husband and five months after her sister. She was only 30 years old.

Her sister Sarah gave birth to a little girl on January 17 1850. Unfortunately, the infant died four weeks later from convulsions. Sarah also married an ex-convict, Robert Harrods.

Harrods could read and write and was closer in age to Sarah, he was 26 years old, and Sarah was seventeen. They were married on April 24 1851. Although his name is not on the birth register, Harrod may have been the first child's father. Sarah had five children, Robert, December 25 1852, John, February 4 1857, Susan, 20, September 1858 and Sarah, born in January 1862. Six months after the birth of young Sarah, her mother, Sarah on died July 29 1862. The cause of death - natural causes. She was 28 years old.

Their children have gone on to build their own generations.

Comments